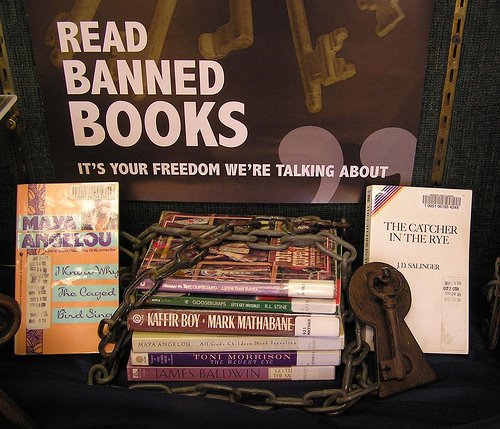

I had planned to read a banned book especially during banned book week but could not, for various reasons. So I decided to make a list of some banned books I've recently (or not so recently) read. These could have been banned in any country/organization. Here goes:

1. Satanic Verses: re-reading

2. The Jewel of Medina

3. The God of Small Things

4. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

5. Animal Farm

6. Ismat Chughtai's 'Lihaf' (technically a short story but one of my faves)

7. The Diary of Anne Frank

8. The Da Vinci Code (technically not literature or even really a book, but heck it was banned in Lebanon)

9. Doctor Zhivago

10. The Grapes of Wrath

11. The Gulap Archipelego (started reading it, but now it sits staring balefully at my from my bedside table)

12. Lady Chatterly's Lover

13. Lajja

14. Lolita

15. 1984

16. The Kite Runner

These are the ones I remember. I know there are many more.

But perhaps more important than a mere listing of books is the question: Why should we read banned books?

This is what I think.

The freedom to think, to read and to write whatever we want is to me a fundamental right. For, if there can be limits to what we can read, what else is left? Policing what we can and cannot read is like posting a cop in our brains. No matter how heinous, gruesome, or disturbing, the freedom of expression relies on the premise that we all need to defend each other's rights to expression despite our own discomforts with these expressions.

Unorthodox viewpoints, unpopular ways of looking at the world and its people creates a tension. A tension that makes us grow and explore and develop in new and unexepected ways. It is important to challenge the status quo, for it is in doing so that humanity develops.

This does not mean that we all have to agree. On the contrary. Instead it creates a free, equal, and open forum for discussion in which those for and against an idea can debate it in the marketplace of ideas.

Constraining thought in a free society points the way towards totalitarianism sometime down the road.

I have the right to read what I want to. You have the right not to. I cannot mandate that you must read what I decide. And you cannot tell me that I cannot read what I want to.

So, during this state of economic instability and the general malaise in the world, let us all put away our lists. Try to read at least one banned book a year. Make yourself heard by picking up a banned book and quietly proclaiming that you believe, truly believe in the freedom of thought and expression. And that, ultimately, you are fully prepared to debate this and all other thoughts you hold dear.

For nothing is sacrosanct. And ultimately, that makes every thought valuable enough to be debated openly, to be discussed honestly. And what better freedom of expression can there be.

Don't wait for the next banned books week. Read a banned book.

Monday, October 5, 2009

Friday, September 25, 2009

Showing a Pink Sari to a Holy Cow!

I've lived a little less than half my life in India, a little more than half in the U.S., and now the last 3 in Switzerland. I've lived all my life as a minority, or really as I like to think of it as an "other." A Muslim in India, an Indian in the west, brown in now my mostly white world. And for 99.9% of the time I don't even think about being the other, about being Indian or brown or whatever hyphenated qualifier comes to mind. I just was. I just am. I live my life. I have friends I cherish. Writers around me who I respect. People of all colors, ethnicities, and assorted backgrounds who form my own personal rainbow. And I write. And even though I sometimes write about my "other" experience, in my normal daily life I rarely dwell on it.

Writing, and everything related to it is sacred to me. As a non-believer in anything divine, writing is the closest to the divine I have. To me, whatever is related to writing is serious. Writers are witnesses: to history, to world events, to culture, to society. We show a mirror to the world and are reflected in it, in return. And the accoutrements of writing that most impassions me (after writing itself) are critique and discussion.

But perhaps I've been spoilt. I spent my years, especially in the U.S., around people---whether in graduate school, in writers' groups, or just with friends and colleagues---who discussed race and gender and other issues in a severely honest manner. Honest but not alienating. Phrases like racial identities and post-colonialism were used from a place of shared understanding. And mutual respect was the foundation. Life has been good. Life is good, still.

A few days ago I heard about Shashi Tharoor's tweeting controvorsy. In a nutshell: someone on Twitter asked Tharoor (now a minister in the Indian government, but once the Under-Secretary General of the UN, also a writer and novelist), "Tell us minister, next time you travel to Kerala, will it be cattle class?" He responded: "Absolutely, in cattle class out of solidarity with all our holy cows."

All hell broke loose. A holy cow? How dare he? The cow is our mother, damnit! She is sacred to us, our mother, they said, unaware of the delicious irony of their responses. The Congress (his own party) declared his statement unacceptable. No matter that he explained that this holy cow had nothing to do with our bountiful and loving "gau mata," that holy cow was an expression of surprise and also a commentary on all those untouchable topics India revels in. You know the uncomfortable ones. The ones that become the white elephant, much larger than any holy cow can dare be. That it was merely a clever play on words. No matter. Indians were outraged and outraged they remain.

When I read this news story last Saturday I chuckled and shook my head in disbelief. And then I set off--unbeknownst to myself then---to tackle my own holy cow. Yes, these divine bovine creatures do not just exist in exotic third world countries. They chew the cud in the comfortable confines of the middle-class West within which I live and write.

I hate confrontation! There...I said it. I love discussions but hate confrontation so most of the time I try to phrase my thoughts in ways that avoid confrontation. Not only because of my inherent discomfort but also because I naively but honestly believe that discussions are conduits that can take us all to higher levels of shared meanings, while confrontations merely set up an 'us and them' dynamic that can alienate and cease discussion.

I also believe in a cliche. You know, "Well-behaved women rarely make history." A wee bit contradictory but that's me, that's most of us. Not that I want to make history. I merely want to know that I fulfill my duties as a small-time writer and a critic. So there I sat in my large writers group listening to a finely told travelogue, affectionate and funny in its tone, about someone's travel to India.

Well-written, except for 4-5 rather obvious stereotypes. Yes, it's true, many Indians wobble their heads, and some of them wear pink saris. But if all the Indians who appear in a three-page story are one stereotype after the other, the writing appears reductionist, not to mention lazy. Yes, stereotypes have a kernel of truth, but as a writer I believe, our job is to push beyond the obvious, to bring forward hidden truths that stereotypes can obscure. And bringing a piece of writing to a critique group means that you want to know how others perceive your work, which the writer in question did. But the discussion had gotten away from her writing--even away from her really--and started lurching towards something else. The holy cow had torn through the pink sari and was now mincing around a mine-field.

I was enjoying this flexing of mental muscle. This was real. Real writers discussing real issues. There was another vocal person on my side of the discussion. I wasn't alone. There was an opportunity for examining stereotyping and for post-colonial critique. Oh joy! Alas, what was a discussion for me, was instead a first push against the flanks of the holy cow. How had I forgotten? You know the research that says that for the majority (note: not all) middle-class white women, racism is not an issue. Only sexism is. And for women of color (see how quickly I classify myself) racism trumps sexism. Forget racism, we were just talking stereotypes---racial stereotypes, but not racism itself.

A fine difference but a difference nonetheless.

For me the discussion turned when it was bemoaned how in the quest to become politically correct, the freedom of speech had been abrogated, especially in France. Say what? Before I could say that the speaker was talking about religious fundamentalism and censorship and other even knottier issues, someone else picked up that thread and continued to wish for the time when she could have said whatever she wanted without a fear of offending anyone? Huh?

I felt like I was in a time-warp of 1950's America. The only reason that 20,30,40 years ago someone could say something, anything, was because the "other" was not empowered enough to respond whether they merely had a point of discussion to contribute not even if they were truly offended or even gutted. It's easy to say whatever you like when the "other" is not allowed to be a party to the debate. For god's sake, Jim Crow only ended forty-odd years ago. almost in my lifetime, certainly in theirs.

Like a blind bull in a china shop I continued and, without using the actual phrase I did a quick recap of post-colonialism to explain why someone from a former colony might think reducing Indians to only being head-wobbling pink sari wearers was stereoypying them. This does not mean that the writer should not feel free to write stereotypes but that s/he should be aware of their perception. It was not a case for censorship but for free discussion....which means that the "other" has a right to be part of the debate.

For anyone who wants to know and doesn't: Post colonialism is when a colonized group that was earlier only defined to the outside world by its colonizer, attempts to take back that power. India's post-colonial literature, in particular is rich, studded with Rushdie's and Chandra's and Roy's works. Post-colonialism Indian literature stands constrasted against the colonial literature, that even when sympathetic to India and Indians, still dealt with them in stereotypical terms. Even some British literature that appeared post-1947 (hello! Raj nostalgia books anyone?). Post-colonial theory was also applied to reviewing and critiquing already existing and emerging literature from a different perspective. Literary criticism from a post-colonial perspective examines works from this same standpoint, of sloughing off the remnants of colonial perceptions and thoughts, and seeing things from an awakened consciousness rooted in our own identities and realities. Until now I had never fully seen what a revolutionary concept this was, how upsetting to certain groups.

Freedom of expression is one of the unshakeable foundations of my own writing. In my own recently completed novel I not only examine prejudice and hatred from the other side but also those of my own.

I believe...truly believe...in the rights of writers and artists to be able to express themselves fully without censorshop or reprisals, no matter how heinous their characterizations. But you know what makes the freedom of expression work? That everyone...yes...even the person being written about (or stereotyped) can participate in the discussion without being shouted down. To bemoan the lack of freedom of expression myself I cannot shut others up. And the discussion needs to exist in a place of mutual respect even if there is severe dissent. There needs to be a willingness to see the other's viewpoint even if there is disagreement. It doesn't exist in a place where traditional power-holders can shame/shut up/disregard/alienate the members of the group being talked about.

Sound familiar, this taking of power from traditional power-holders? Some of those so clearly upset (even though their upset was displayed through disapproving silence) were women who had probably come of age during the sexual revolution. You know....when *men* were finally told that they could not dictate to women about their own bodies. I've been in solidarity with my fellow-Western women when they proclaimed "get your hands off my body," and when they protested the unfairness of old, white men telling them about what they could or could not do with their own bodies.

But what of the rest of me? The non-body part of me? Is it less valuable? I have an identity beyond my gender...we all do. And that part too has the right to say, "take your stereotypes, your constructs off my identity...or at least understand that when you write what you do and say what you that this is the meaning I take from it." And for the first time I also wondered about their solidarity with me, with others like me?

A writer has the right to continue to write in stereotypes. I would fight for her right to do so. But conversely another writer or reader also has the right to draw attention to this, to respond, to proclaim an identity beyond reductionisms.

You know how you know something only as a theory but have not experienced it as a reality. This encounter was an eye-opener for me, a moment in time when a theory collided with reality and left me to examine and re-examine my place in my environment. Alone and alienated, with people refusing to meet my eyes, and others who clapped in solidarity against the two of us, the two women of color who had the temerity to draw attention to a stereotype. To me stereotypes are not always necessarily racist (which in this case they were really not) but are merely lazy codes.

I am still making sense of this episode. From wishing I had kept my mouth shut to wishing I had made my points in a more articulate manner. But above it all, remains my discomfiture, a certain fluttering in my stomach that reminds me why I hate confrontation. It reminds me that no matter how sophististicated and literate a group, holy cows are to be worshipped and woe betide anyone who dares straddle one.

But above all it underscores a loneliness I have not felt in recent years and an alienation I had not remembered until now.

Perhaps in retrospect I will make more sense of it, maybe I'll even find some humor in it, or some lasting lesson. That is my hope. What more can we ask for in life, after all except hope?

Writing, and everything related to it is sacred to me. As a non-believer in anything divine, writing is the closest to the divine I have. To me, whatever is related to writing is serious. Writers are witnesses: to history, to world events, to culture, to society. We show a mirror to the world and are reflected in it, in return. And the accoutrements of writing that most impassions me (after writing itself) are critique and discussion.

But perhaps I've been spoilt. I spent my years, especially in the U.S., around people---whether in graduate school, in writers' groups, or just with friends and colleagues---who discussed race and gender and other issues in a severely honest manner. Honest but not alienating. Phrases like racial identities and post-colonialism were used from a place of shared understanding. And mutual respect was the foundation. Life has been good. Life is good, still.

A few days ago I heard about Shashi Tharoor's tweeting controvorsy. In a nutshell: someone on Twitter asked Tharoor (now a minister in the Indian government, but once the Under-Secretary General of the UN, also a writer and novelist), "Tell us minister, next time you travel to Kerala, will it be cattle class?" He responded: "Absolutely, in cattle class out of solidarity with all our holy cows."

All hell broke loose. A holy cow? How dare he? The cow is our mother, damnit! She is sacred to us, our mother, they said, unaware of the delicious irony of their responses. The Congress (his own party) declared his statement unacceptable. No matter that he explained that this holy cow had nothing to do with our bountiful and loving "gau mata," that holy cow was an expression of surprise and also a commentary on all those untouchable topics India revels in. You know the uncomfortable ones. The ones that become the white elephant, much larger than any holy cow can dare be. That it was merely a clever play on words. No matter. Indians were outraged and outraged they remain.

When I read this news story last Saturday I chuckled and shook my head in disbelief. And then I set off--unbeknownst to myself then---to tackle my own holy cow. Yes, these divine bovine creatures do not just exist in exotic third world countries. They chew the cud in the comfortable confines of the middle-class West within which I live and write.

I hate confrontation! There...I said it. I love discussions but hate confrontation so most of the time I try to phrase my thoughts in ways that avoid confrontation. Not only because of my inherent discomfort but also because I naively but honestly believe that discussions are conduits that can take us all to higher levels of shared meanings, while confrontations merely set up an 'us and them' dynamic that can alienate and cease discussion.

I also believe in a cliche. You know, "Well-behaved women rarely make history." A wee bit contradictory but that's me, that's most of us. Not that I want to make history. I merely want to know that I fulfill my duties as a small-time writer and a critic. So there I sat in my large writers group listening to a finely told travelogue, affectionate and funny in its tone, about someone's travel to India.

Well-written, except for 4-5 rather obvious stereotypes. Yes, it's true, many Indians wobble their heads, and some of them wear pink saris. But if all the Indians who appear in a three-page story are one stereotype after the other, the writing appears reductionist, not to mention lazy. Yes, stereotypes have a kernel of truth, but as a writer I believe, our job is to push beyond the obvious, to bring forward hidden truths that stereotypes can obscure. And bringing a piece of writing to a critique group means that you want to know how others perceive your work, which the writer in question did. But the discussion had gotten away from her writing--even away from her really--and started lurching towards something else. The holy cow had torn through the pink sari and was now mincing around a mine-field.

I was enjoying this flexing of mental muscle. This was real. Real writers discussing real issues. There was another vocal person on my side of the discussion. I wasn't alone. There was an opportunity for examining stereotyping and for post-colonial critique. Oh joy! Alas, what was a discussion for me, was instead a first push against the flanks of the holy cow. How had I forgotten? You know the research that says that for the majority (note: not all) middle-class white women, racism is not an issue. Only sexism is. And for women of color (see how quickly I classify myself) racism trumps sexism. Forget racism, we were just talking stereotypes---racial stereotypes, but not racism itself.

A fine difference but a difference nonetheless.

For me the discussion turned when it was bemoaned how in the quest to become politically correct, the freedom of speech had been abrogated, especially in France. Say what? Before I could say that the speaker was talking about religious fundamentalism and censorship and other even knottier issues, someone else picked up that thread and continued to wish for the time when she could have said whatever she wanted without a fear of offending anyone? Huh?

I felt like I was in a time-warp of 1950's America. The only reason that 20,30,40 years ago someone could say something, anything, was because the "other" was not empowered enough to respond whether they merely had a point of discussion to contribute not even if they were truly offended or even gutted. It's easy to say whatever you like when the "other" is not allowed to be a party to the debate. For god's sake, Jim Crow only ended forty-odd years ago. almost in my lifetime, certainly in theirs.

Like a blind bull in a china shop I continued and, without using the actual phrase I did a quick recap of post-colonialism to explain why someone from a former colony might think reducing Indians to only being head-wobbling pink sari wearers was stereoypying them. This does not mean that the writer should not feel free to write stereotypes but that s/he should be aware of their perception. It was not a case for censorship but for free discussion....which means that the "other" has a right to be part of the debate.

For anyone who wants to know and doesn't: Post colonialism is when a colonized group that was earlier only defined to the outside world by its colonizer, attempts to take back that power. India's post-colonial literature, in particular is rich, studded with Rushdie's and Chandra's and Roy's works. Post-colonialism Indian literature stands constrasted against the colonial literature, that even when sympathetic to India and Indians, still dealt with them in stereotypical terms. Even some British literature that appeared post-1947 (hello! Raj nostalgia books anyone?). Post-colonial theory was also applied to reviewing and critiquing already existing and emerging literature from a different perspective. Literary criticism from a post-colonial perspective examines works from this same standpoint, of sloughing off the remnants of colonial perceptions and thoughts, and seeing things from an awakened consciousness rooted in our own identities and realities. Until now I had never fully seen what a revolutionary concept this was, how upsetting to certain groups.

Freedom of expression is one of the unshakeable foundations of my own writing. In my own recently completed novel I not only examine prejudice and hatred from the other side but also those of my own.

I believe...truly believe...in the rights of writers and artists to be able to express themselves fully without censorshop or reprisals, no matter how heinous their characterizations. But you know what makes the freedom of expression work? That everyone...yes...even the person being written about (or stereotyped) can participate in the discussion without being shouted down. To bemoan the lack of freedom of expression myself I cannot shut others up. And the discussion needs to exist in a place of mutual respect even if there is severe dissent. There needs to be a willingness to see the other's viewpoint even if there is disagreement. It doesn't exist in a place where traditional power-holders can shame/shut up/disregard/alienate the members of the group being talked about.

Sound familiar, this taking of power from traditional power-holders? Some of those so clearly upset (even though their upset was displayed through disapproving silence) were women who had probably come of age during the sexual revolution. You know....when *men* were finally told that they could not dictate to women about their own bodies. I've been in solidarity with my fellow-Western women when they proclaimed "get your hands off my body," and when they protested the unfairness of old, white men telling them about what they could or could not do with their own bodies.

But what of the rest of me? The non-body part of me? Is it less valuable? I have an identity beyond my gender...we all do. And that part too has the right to say, "take your stereotypes, your constructs off my identity...or at least understand that when you write what you do and say what you that this is the meaning I take from it." And for the first time I also wondered about their solidarity with me, with others like me?

A writer has the right to continue to write in stereotypes. I would fight for her right to do so. But conversely another writer or reader also has the right to draw attention to this, to respond, to proclaim an identity beyond reductionisms.

You know how you know something only as a theory but have not experienced it as a reality. This encounter was an eye-opener for me, a moment in time when a theory collided with reality and left me to examine and re-examine my place in my environment. Alone and alienated, with people refusing to meet my eyes, and others who clapped in solidarity against the two of us, the two women of color who had the temerity to draw attention to a stereotype. To me stereotypes are not always necessarily racist (which in this case they were really not) but are merely lazy codes.

I am still making sense of this episode. From wishing I had kept my mouth shut to wishing I had made my points in a more articulate manner. But above it all, remains my discomfiture, a certain fluttering in my stomach that reminds me why I hate confrontation. It reminds me that no matter how sophististicated and literate a group, holy cows are to be worshipped and woe betide anyone who dares straddle one.

But above all it underscores a loneliness I have not felt in recent years and an alienation I had not remembered until now.

Perhaps in retrospect I will make more sense of it, maybe I'll even find some humor in it, or some lasting lesson. That is my hope. What more can we ask for in life, after all except hope?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)